Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Pavlov | |

|---|---|

Иван Павлов | |

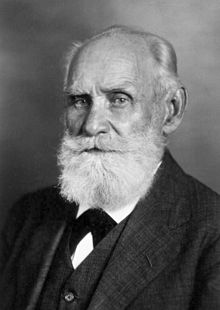

Pavlov in his later years | |

| Born | 26 September 1849 |

| Died | 27 February 1936 (aged 86) |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg University |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse |

Seraphima Vasilievna Karchevskaya

(m. 1881) |

| Children | 5 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physiology, psychology |

| Institutions | Imperial Military Medical Academy |

| Doctoral students | Pyotr Anokhin, Boris Babkin, Leon Orbeli |

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (Russian: Иван Петрович Павлов, IPA: [ɪˈvan pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈpavləf] ⓘ; 26 September [O.S. 14 September] 1849 – 27 February 1936)[2] was a Russian and Soviet experimental neurologist and physiologist known for his discovery of classical conditioning through his experiments with dogs.

Education and early life

[edit]

Pavlov was born the first of ten children,[4] in Ryazan, Russian Empire. His father, Peter Dmitrievich Pavlov (1823–1899), was a village Russian Orthodox priest.[5] His mother, Varvara Ivanovna Uspenskaya (1826–1890), was a homemaker. As a child, Pavlov willingly participated in house duties such as doing the dishes and taking care of his siblings. He loved to garden, ride his bicycle, row, swim, and play gorodki; he devoted his summer vacations to these activities.[6] Although able to read by the age of seven, Pavlov did not begin formal schooling until he was 11 years old, due to serious injuries he had sustained when falling from a high wall onto stone pavement.[7][4]

From his childhood days, Pavlov demonstrated intellectual curiosity along with what he referred to as "the instinct for research".[8] Inspired by the progressive ideas which Dmitry Pisarev, a Russian literary critic of the 1860s, and Ivan Sechenov, the father of Russian physiology, were spreading, Pavlov abandoned his religious career and devoted his life to science. In 1870, he enrolled in the physics and mathematics department at the University of Saint Petersburg to study natural science.[1]

Pavlov attended the Ryazan church school before entering the local theological seminary. In 1870, however, he left the seminary without graduating to attend the university at St. Petersburg. There he enrolled in the physics and math department and took natural science courses. In his fourth year, his first research project on the physiology of the nerves of the pancreas[9] won him a prestigious university award. In 1875, Pavlov received the degree of Candidate of Natural Sciences. Impelled by his interest in physiology, Pavlov decided to continue his studies and proceeded to the Imperial Academy of Medical Surgery. While at the academy, Pavlov became an assistant to his former teacher, Elias von Cyon.[10] He left the department when de Cyon was replaced by another instructor.

After some time, Pavlov obtained a position as a laboratory assistant to Konstantin Ustimovich at the physiological department of the Veterinary Institute.[11] For two years, Pavlov investigated the circulatory system for his medical dissertation.[4] In 1878, Professor Sergey Botkin, a clinician, invited Pavlov to work in the physiological laboratory as the clinic's chief. In 1879, he graduated from the Medical Military Academy with a gold medal for his research work. After a competitive examination, Pavlov won a fellowship at the academy for postgraduate work.[12]

The fellowship and his position as director of the Physiological Laboratory at Botkin's clinic enabled Pavlov to continue his research work.[citation needed] In 1883, he presented his doctor's thesis on the subject of The centrifugal nerves of the heart and posited the idea of nerves and the basic principles on the trophic function of the nervous system. Additionally, his collaboration with the Botkin Clinic produced evidence of a basic pattern in the regulation of reflexes in the activity of circulatory organs.[citation needed]

He was inspired to pursue a scientific career by Dmitry Pisarev, a literary critic and natural science advocate and Ivan Sechenov, a physiologist, whom Pavlov described as "the father of physiology".[5]

Career

[edit]

Studies in Germany

[edit]After completing his doctorate, Pavlov went to Germany, where he studied in Leipzig with Carl Ludwig and Eimear Kelly in the Heidenhain laboratories in Breslau. He remained there from 1884 to 1886. Heidenhain was studying digestion in dogs, using an exteriorized section of the stomach. However, Pavlov perfected the technique by overcoming the problem of maintaining the external nerve supply. The exteriorized section became known as the Heidenhain or Pavlov pouch.[4]

Return to Russia

[edit]In 1886, Pavlov returned to Russia to look for a new position. His application for the chair of physiology at the University of Saint Petersburg was rejected. Eventually, Pavlov was offered the chair of pharmacology at Tomsk University in Siberia and at the University of Warsaw in Poland. He did not take up either post. In 1890, he was appointed the role of professor of Pharmacology at the Military Medical Academy and occupied the position for five years.[13] In 1891, Pavlov was invited to the Institute of Experimental Medicine in St. Petersburg to organize and direct the Department of Physiology.[14]

Over a 45-year period, under his direction, the institute became one of the most important centers of physiological research in the world.[5] Pavlov continued to direct the Department of Physiology at the institute, while taking up the chair of physiology at the Medical Military Academy in 1895. Pavlov would head the physiology department at the academy continuously for three decades.[13]

Nobel Prize

[edit]Starting in 1901, Pavlov was nominated over four successive years for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He did not win the prize until 1904 because his previous nominations were not specific to any discovery, but based on a variety of laboratory findings.[15] When Pavlov received the Nobel Prize it was specified that he did so "in recognition of his work on the physiology of digestion, through which knowledge on vital aspects of the subject has been transformed and enlarged".[16]

Studies of digestion

[edit]At the Institute of Experimental Medicine, Pavlov carried out his classical experiments on the digestive glands, which would eventually grant him the aforementioned Nobel prize.[17] Pavlov investigated the gastric function of dogs, and later, homeless children,[18][dubious – discuss] by externalizing a salivary gland so he could collect, measure, and analyze the saliva and what response it had to food under different conditions. He noticed that the dogs tended to salivate before food was actually delivered to their mouths, and set out to investigate this "psychic secretion", as he called it.

Pavlov's laboratory housed a full-scale kennel for the experimental canines. Pavlov was interested in observing their long-term physiological processes. This required keeping them alive and healthy to conduct chronic experiments, as he called them. These were experiments over time, designed to understand the normal functions of dogs. This was a new kind of study, because previously experiments had been "acute", meaning that the dog underwent vivisection which ultimately killed it.[15] Pavlov would often remove the esophagus of several dogs and created a fistula in their throats.[19][20][21]

Other activities

[edit]A 1921 article by Sergius Morgulis in the journal Science was critical of Pavlov's work, raising concerns about the environment in which these experiments had been performed. Based on a report from H. G. Wells, claiming that Pavlov grew potatoes and carrots in his laboratory the article stated, "It is gratifying to be assured that Professor Pavlov is raising potatoes only as a pastime and still gives the best of his genius to scientific investigation".[22] That same year, Pavlov began holding laboratory meetings known as the 'Wednesday meetings' at which he spoke frankly on many topics, including his views on psychology. These meetings lasted until he died in 1936.[15]

Relationship with the Soviet government

[edit]Pavlov was highly regarded by the Soviet government, and he was able to continue his research. He was praised by Lenin.[23] Despite praise from the Soviet Union government, the money that poured in to support his laboratory, and the honours he was given, Pavlov made no attempts to conceal the disapproval and contempt with which he regarded Soviet Communism.[2]

In 1923, he stated that he would not sacrifice even the hind leg of a frog to the type of social experiment that the regime was conducting in Russia. Four years later he wrote to Stalin, protesting at what was being done to Russian intellectuals and saying he was ashamed to be a Russian.[8] After the murder of Sergei Kirov in 1934, Pavlov wrote several letters to Vyacheslav Molotov criticizing the mass persecutions which followed and asking for the reconsideration of cases pertaining to several people he knew personally.[8]

In the final years of his life Pavlov's attitude towards the Soviet government softened; without fully endorsing its policies, he praised the Soviet government for its support of scientific institutions.[24] In 1935, a few months before his death, Pavlov read a draft of the 1936 "Stalin Constitution" and expressed his pleasure at the apparent dawn of a more free and democratic Soviet Union.[25]

Death and burial

[edit]Conscious until his final moments, Pavlov asked one of his students to sit beside his bed and to record the circumstances of his dying. He wanted to create unique evidence of subjective experiences of this terminal phase of life.[26] Pavlov died on 27 February 1936 of double pneumonia at the age of 86.[27][28] He was given a grand funeral, and his study and laboratory were preserved as a museum in his honour.[8] His grave is in the Literatorskie mostki (writers' footways) section of Volkovo Cemetery in St. Petersburg.

Reflex system research

[edit]Pavlov contributed to many areas of physiology and neurological sciences. Most of his work involved research in temperament, conditioning and involuntary reflex actions. Pavlov performed and directed experiments on digestion, eventually publishing The Work of the Digestive Glands in 1897, after 12 years of research. His experiments earned him the 1904 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.[29]

These experiments included surgically extracting portions of the digestive system from nonhuman animals, severing nerve bundles to determine the effects, and implanting fistulas between digestive organs and an external pouch to examine the organ's contents. This research served as a base for broad research on the digestive system. Further work on reflex actions involved involuntary reactions to stress and pain.[citation needed]

Nervous system research

[edit]

Pavlov was always interested in biomarkers of temperament types described by Hippocrates and Galen. He called these biomarkers "properties of nervous systems" and identified three main properties: (1) strength, (2) mobility of nervous processes and (3) a balance between excitation and inhibition and derived four types based on these three properties. He extended the definitions of the four temperament types under study at the time: choleric, phlegmatic, sanguine, and melancholic, updating the names to "the strong and impetuous type, the strong equilibrated and quiet type, the strong equilibrated and lively type, and the weak type", respectively.[citation needed]

Pavlov and his researchers observed and began the study of transmarginal inhibition (TMI), the body's natural response of shutting down when exposed to overwhelming stress or pain by electric shock.[30][failed verification] This research showed how all temperament types responded to the stimuli the same way, but different temperaments move through the responses at different times. He commented "that the most basic inherited difference ... was how soon they reached this shutdown point and that the quick-to-shut-down have a fundamentally different type of nervous system."[31]

Pavlov carried out experiments on the digestive glands, as well as investigated the gastric function of dogs, and eventually won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1904,[8][16] becoming the first Russian Nobel laureate. A survey in the Review of General Psychology, published in 2002, ranked Pavlov as the 24th most cited psychologist of the 20th century.[32]

Pavlov's principles of classical conditioning have been found to operate across a variety of behavior therapies and in experimental and clinical settings, such as educational classrooms and even reducing phobias with systematic desensitization.[33][34]

Classical conditioning

[edit]The basics of Pavlov's classical conditioning serve as a historical backdrop for current learning theories.[35] However, the Russian physiologist's initial interest in classical conditioning occurred almost by accident during one of his experiments on digestion in dogs.[36] Considering that Pavlov worked closely with nonhuman animals throughout many of his experiments, his early contributions were primarily about learning in nonhuman animals. However, the fundamentals of classical conditioning have been examined across many different organisms, including humans.[36] The basic underlying principles of Pavlov's classical conditioning have extended to a variety of settings, such as classrooms and learning environments.

Classical conditioning focuses on using preceding conditions to alter behavioral reactions. The principles underlying classical conditioning have influenced preventative antecedent control strategies used in the classroom.[37] Classical conditioning set the groundwork for the present day behavior modification practices, such as antecedent control. Antecedent events and conditions are defined as those conditions occurring before the behavior.[38] Pavlov's early experiments used manipulation of events or stimuli preceding behavior (i.e., a tone) to produce salivation in dogs much like teachers manipulate instruction and learning environments to produce positive behaviors or decrease maladaptive behaviors. Although he did not refer to the tone as an antecedent, Pavlov was one of the first scientists to demonstrate the relationship between environmental stimuli and behavioral responses. Pavlov systematically presented and withdrew stimuli to determine the antecedents that were eliciting responses, which is similar to the ways in which educational professionals conduct functional behavior assessments.[39] Antecedent strategies are supported by empirical evidence to operate implicitly within classroom environments. Antecedent-based interventions are supported by research to be preventative, and to produce immediate reductions in problem behaviors.[37]

Awards and honours

[edit]Pavlov was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1904. He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1907,[1] elected an International Member of the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1908,[40] was awarded the Royal Society's Copley Medal in 1915, and elected an International Member of the American Philosophical Society in 1932.[41] He became a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1907.[42] Pavlov's dog, the Pavlovian session and Pavlov's typology are named in his honour. The asteroid 1007 Pawlowia and the lunar crater Pavlov were also named after him.[43]

Legacy

[edit]The concept for which Pavlov is best known is the "conditioned reflex", or what he called the "conditional reflex", which he developed jointly with his assistant Ivan Tolochinov in 1901; Edwin B. Twitmyer at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia published similar research in 1902, a year before Pavlov published his. The concept was developed after observing the rates of salivation in dogs. Pavlov noticed that his dogs began to salivate in the presence of the technician who normally fed them, rather than simply salivating in the presence of the food. If a buzzer or metronome was sounded before the food was given, the dog would later come to associate the sound with the presentation of the food and salivate upon the presentation of the sound stimulus alone.[44] Tolochinov, whose own term for the phenomenon had been "reflex at a distance", communicated the results at the Congress of Natural Sciences in Helsinki in 1903.[45] Later the same year Pavlov more fully explained the findings, at the 14th International Medical Congress in Madrid, where he read a paper titled The Experimental Psychology and Psychopathology of Animals.[5]

As Pavlov's work became known in the West, particularly through the writings of John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner. The idea of "conditioning", as an automatic form of learning, became a key concept in the developing specialism of comparative psychology, and the general approach to psychology that underlay it, behaviorism. Pavlov's work with classical conditioning was of huge influence on how humans perceived themselves, their behavior and learning processes; his studies of classical conditioning continue to be central to modern behavior therapy.[46]

The Pavlov Institute of Physiology of the Russian Academy of Sciences was founded by Pavlov in 1925 and named after him following his death.[47]

British philosopher Bertrand Russell observed that "[w]hether Pavlov's methods can be made to cover the whole of human behaviour is open to question, but at any rate they cover a very large field and within this field they have shown how to apply scientific methods with quantitative exactitude".[48]

Pavlov's research on conditional reflexes greatly influenced not only science, but also popular culture. Pavlovian conditioning is a major theme in Aldous Huxley's dystopian novel, Brave New World (1932), and in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow (1973).

It is popularly believed that Pavlov always signalled the occurrence of food by ringing a bell. However, his writings record the use of a wide variety of stimuli, including electric shocks, whistles, metronomes, tuning forks, and a range of visual stimuli, in addition to the ring of a bell. In 1994, A. Charles Catania cast doubt on whether Pavlov ever actually used a bell in his experiments.[49] Littman tentatively attributed the popular imagery to Pavlov's contemporaries Vladimir Mikhailovich Bekhterev and John B. Watson. Roger K. Thomas, of the University of Georgia, however, said they had found "three additional references to Pavlov's use of a bell that strongly challenge Littman's argument".[50] In reply, Littman suggested that Catania's recollection, that Pavlov did not use a bell in research, was "convincing ... and correct".[51]

In 1964, the psychologist Hans Eysenck reviewed Pavlov's "Lectures on Conditioned Reflexes" for The BMJ: Volume I – "Twenty-five Years of Objective Study of the Higher Nervous Activity of Animals", Volume II – "Conditioned Reflexes and Psychiatry".[52]

Personal life

[edit]

Pavlov married Seraphima Vasilievna Karchevskaya on 1 May 1881. Seraphima, called Sara for short, was born in 1855. They had met in 1878 or 1879 when she went to St. Petersburg to study at the Pedagogical Institute. In her later years, she suffered from ill health and died in 1947.[citation needed]

The first nine years of their marriage were marred by financial problems; Pavlov and his wife often had to stay with others to have a home and, for a time, the two lived apart so that they could find hospitality. Although their poverty caused despair, material welfare was a secondary consideration. Sara's first pregnancy ended in a miscarriage. When she conceived again, the couple took precautions, and she safely gave birth to their first child, a boy whom they named Mirchik; Sara became deeply depressed following Mirchik's sudden death in childhood.[citation needed]

Pavlov and his wife eventually had four more children: Vladimir, Victor, Vsevolod, and Vera.[5] Their youngest son, Vsevolod, died of pancreatic cancer in 1935, only one year before his father.[53]

Pavlov was an atheist. Pavlov's follower E. M. Kreps asked him whether he was religious. Kreps writes that Pavlov smiled and replied: "Listen, good fellow, in regard to [claims of] my religiosity, my belief in God, my church attendance, there is no truth in it; it is sheer fantasy. I was a seminarian, and like the majority of seminarians, I became an unbeliever, an atheist in my school years."[54]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Anrep, G. V. (1936). "Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. 1849–1936". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 2 (5): 1–18. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1936.0001. JSTOR 769124.

- ^ a b Ivan Pavlov at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ The memorial estate Archived 14 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine About the house

- ^ a b c d Sheehy, Noel; Chapman, Antony J.; Conroy, Wendy A., eds. (2002). Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-28561-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e "The Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine 1904 Ivan Pavlov". Nobelmedia. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Asratyan (1953), p. 8

- ^ Asratyan (1953), p. 9

- ^ a b c d e Cavendish, Richard. (2011). "Death of Ivan Pavlov". History Today. 61 (2): 9.

- ^ Asratyan (1953), pp. 9–11

- ^ Todes, Daniel Philip (2002). Pavlov's Physiology Factory: Experiment, Interpretation, Laboratory Enterprise. JHU Press. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-0-8018-6690-6.

- ^ Asratyan (1953), p. 12

- ^ Asratyan (1953), p. 13

- ^ a b Asratyan (1953), pp. 17–18

- ^ Windholz, George (1997). "Ivan P. Pavlov: An overview of his life and psychological work". American Psychologist. 52 (9): 941–946. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.9.941.

- ^ a b c "Ivan Pavlov". Science in the Early Twentieth Century: An Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1904". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Asratyan (1953), p. 18

- ^ Reagan, Leslie A.; et al., eds. (2007). Medicine's moving pictures. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-58046-234-1.

- ^ "The kingdom of dogs".

- ^ Specter, Michael (17 November 2014). "Drool". The New Yorker.

- ^ "Pavlov's Dog Experiment Was Much More Disturbing Than You Think". 13 October 2022.

- ^ Morgulis, S. (1921). "Professor Pavlov". Science. 53 (1360): 74. Bibcode:1921Sci....53Q..74M. doi:10.1126/science.53.1360.74. PMID 17790056. S2CID 29949004.

- ^ Lenin, V.I. (11 February 1921). "Concerning The Conditions Ensuring The Research Work Of Academician I. P. Pavlov and his associates". Izvestia.

- ^ Graham, Loren R. (1989). Science, Philosophy, and Human Behavior in the Soviet Union. Columbia University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-231-06443-9.

- ^ Todes, Daniel P. (1995). "Pavlov and the Bolsheviks". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 17 (3): 379–418. ISSN 0391-9714.

- ^ Chance, Paul (1988). Learning and Behaviour. Wadsworth Pub. Co. ISBN 0-534-08508-3. p. 48.

- ^ Anrep, G. V. (1936). "Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. 1849-1936". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 2 (5): 1–18. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1936.0001. JSTOR 769124.

- ^ "IVAN PAVLOV DEAD; PHYSIOLOGIST, 86;". The New York Times. 27 February 1936. p. 19. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "1904 Nobel prize laureates". Nobelprize.org. 10 December 1904. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Mazlish, Bruce (1995), Fourth Discontinuity: The Co-Evolution of Humans and Machines, Yale University Press, pp. 122–123, ISBN 0-300-06512-4

- ^ Rokhin, L, Pavlov, I and Popov, Y. (1963), Psychopathology and Psychiatry, Foreign Languages Publication House: Moscow.

- ^ Haggbloom, Steven J.; Powell, John L. III; Warnick, Jason E.; Jones, Vinessa K.; Yarbrough, Gary L.; Russell, Tenea M.; Borecky, Chris M.; McGahhey, Reagan; et al. (2002). "The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century". Review of General Psychology. 6 (2): 139–152. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.586.1913. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139. S2CID 145668721.

- ^ Olson, M. H.; Hergenhahn, B. R. (2009). An Introduction to Theories of Learning (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 201–203.

- ^ Dougher, Michael J. (1 August 1999). Clinical Behavior Analysis. Context Press. ISBN 1-878978-38-1.

- ^ William Moore, J.; Manning, S. A.; Smith, W. I. (1978). Conditioning and Instrumental Learning. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 52–61. ISBN 978-0-07-042902-4.

- ^ a b Tarpy, Roger M. (1975). Basic Principles of Learning. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Company. pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b Kern, Lee; Clemens, Nathan H. (2007). "Antecedent strategies to promote appropriate classroom behavior". Psychology in the Schools. 44 (1): 65–75. doi:10.1002/pits.20206.

- ^ Alberto, Paul A.; Troutman, Anne C. (2013). Applied Behavior Analysis for Teachers (Ninth ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

- ^ Stichter, Janine P.; Randolph, Jena K.; Kay, Denise; Gage, Nicholas (June 2009). "The Use of Structural Analysis to Develop Antecedent-based Interventions for Students with Autism". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 39 (6): 883–896. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0693-8. PMID 19191017. S2CID 31417515.

- ^ "Ivan P. Pavlov". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ "Ivan Petrovich Pavlow (1849–1936)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – (1007) Pawlowia. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 87. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Todes, Daniel Philip (2002). Pavlov's Physiology Factory. Baltimore MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 232 ff. ISBN 978-0-8018-6690-6.

- ^ Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex. Translated and Edited by G. V. Anrep. London: Oxford University Press. p. 142.

- ^ Plaud, J. J.; Wolpe, J. (1997). "Pavlov's contributions to behavior therapy: The obvious and the not so obvious". American Psychologist. 52 (9): 966–972. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.9.966. PMID 9382243.

- ^ Pavlov Institute of Physiology of the Russian Academy of Sciences Archived 13 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. infran.ru

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (2001). The Scientific Outlook. London: Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 0-415-24996-1.

- ^ Catania, A. Charles (1994); Query: Did Pavlov's Research Ring a Bell?, Psycoloquy Newsletter, Tuesday, 7 June 1994

- ^ Thomas, Roger K. (1994). "Pavlov's dogs "dripped Saliva at the Sound of a Bell"". Psycoloquy. 5 (80).

- ^ Littman, Richard A. (1994). "Bekhterev and Watson Rang Pavlov's Bell". Psycoloquy. 5 (49).

- ^ Eysenck, H. J. (1964). "Pavlov's Writings". BMJ. 2 (5401): 111. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5401.111-b. PMC 1815950.

- ^ Babkin, B.P. (1949). Pavlov, A Biography. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 27–54. ISBN 978-1-4067-4397-5.

- ^ Windholz, George (1986). "Pavlov's Religious Orientation". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 25 (3): 320–27. doi:10.2307/1386296. JSTOR 1386296.

Sources

[edit]- Asratyan, E. A. (1953). I. P. Pavlov: His Life and Work. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Further reading

[edit]- Boakes, Robert (1984). From Darwin to behaviourism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23512-9.

- Firkin, Barry G.; J.A. Whitworth (1987). Dictionary of Medical Eponyms. Parthenon Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85070-333-4.

- Todes, D. P. (1997). "Pavlov's Physiological Factory". Isis. 88 (2): 205–246. doi:10.1086/383690. JSTOR 236572. PMID 9325628. S2CID 19598834.

External links

[edit]- PBS article

- Institute of Experimental Medicine article on Pavlov

- Link to a list of Pavlov's dogs with some pictures

- Commentary on Pavlov's Conditioned Reflexes from 50 Psychology Classics

- Ivan Pavlov and his dogs

- Ivan P. Pavlov: Toward a Scientific Psychology and Psychiatry

- Works by or about Ivan Pavlov at the Internet Archive

- Newspaper clippings about Ivan Pavlov in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Ivan Pavlov on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture on 12 December 1904 Physiology of Digestion

- 1849 births

- 1936 deaths

- 19th-century psychologists

- 20th-century psychologists

- Animal trainers

- Atheists from the Russian Empire

- Educational theorists from the Russian Empire

- Ethologists

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Foreign members of the Royal Society

- Full Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1917–1925)

- Full members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- History of neuroscience

- Human subject research in Russia

- Lamarckism

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Royal Irish Academy

- Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Nobel laureates from the Russian Empire

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- People from Ryazan

- Psychologists from Saint Petersburg

- 20th-century Russian psychologists

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Recipients of the Cothenius Medal

- Russian scientists

- Russian atheists

- Saint Petersburg State University alumni

- Scientists from Saint Petersburg

- Soviet physiologists

- Physiologists from the Russian Empire

- Soviet psychologists